The risk assessment process generally has five steps:

- Identify hazards. This step helps you understand what hazards may occur in the planning area.

- Describe hazards. This step helps you know more about the hazards. It looks at where they can happen, how impactful they might be, when they happened before, how often and with what intensity they may occur in the future.

- Identify community assets: This step looks at which assets are most vulnerable to loss during a disaster.

- Analyze impacts. This step describes how each hazard could affect the assets of each community.

- Summarize vulnerability. This step brings all the analysis together. It uses the risk assessment to draw conclusions. From these conclusions, the planning team can develop a strategy to increase the resilience of residents, businesses, the economy and other vital assets.

4.2.1. Identify Hazards

The first step in the risk assessment is to identify the hazards that affect your planning area. This includes assets in other jurisdictions that may affect yours, like an upstream dam or levee. To identify hazards:

- Review your state’s hazard mitigation plan. These plans summarize risk statewide. If the state identified that your planning area is at risk, it should probably be in your plan. If the state has identified a hazard for your area, and the planning team decides to exclude it, explain why.

- Look at recent mitigation plans developed for nearby areas.

- Interview your planning team, stakeholders and the public. Ask them which hazards affect the planning area and should be in the mitigation plan.

- Check local sources of information. Look into newspapers. Speak with the chamber of commerce, historical societies, or other groups with records of past events.

- For plan updates, start with the previously identified hazards. If they are no longer relevant, explain why. Add any new hazard events that have happened since the last plan update, including all declared disasters.

4.2.2. Describe Hazards

After you know which hazards you want to address, describe them in what is commonly called a hazard profile. The profiles must describe each identified hazard’s location, extent, previous occurrences and probability of future events. Plan updates should confirm the profile for any previously identified hazards and add one for new hazards. Plan updates must include any hazard events that have occurred since the last plan was completed.

4.2.2.1 Location

Location is the geographic area within the planning area that is affected by the hazard. When considering location, think about assets outside the planning area that, if damaged, could cause a hazard to happen in your planning area. For example, a dam or levee may be upstream and outside of the planning area. If it fails, it could flood downstream. A fault line in a neighboring county could cause an earthquake that is felt in your planning area. Some locations may also be further defined, such as high wildfire hazard areas versus low wildfire hazard areas. The entire planning area may be uniformly affected by some hazards. If this is the case, your plan must say so.

Maps are one of the best ways to illustrate location for many hazards. You can also describe location in a narrative. If you use a narrative, describe the locations in detail to clarify where the issues are. To describe the location of the hazards in the planning area:

- Review studies, reports and plans related to your identified hazards. State and federal agencies are good sources for this information.

- Use flood-related products that FEMA made for your planning area. Regulatory and non-regulatory products can be found at the Map Service Center. These include FIRMs and other flood risk assessment products. FEMA makes these to support the NFIP and the Risk MAP program.

- Contact colleges or universities. They may have related academic programs or extension services.

4.2.2.2 Extent

Extent is the expected range of intensity for each hazard. It answers, “How bad can it get?” Often a scientific scale is used to help define extent. Use a narrative and/or maps to describe extent. And remember, if the extent differs across participants in a multi-jurisdictional plan, explain those variations.

How you describe extent depends on the hazard. Examples include:

- The value on an established scientific scale or measurement system, such as EF2 on the Enhanced Fujita Scale for tornadoes or 5.5 on the Richter Scale for earthquakes.

- Water depth, hail size or wind speed.

- Number of acres or feet lost to wildfire, erosion or landslides.

- Highest and lowest recorded temperatures.

- Other measures of magnitude.

The extent of a hazard is not its potential impact on a community. Extent defines the characteristics of the hazard regardless of the people, property and other assets it affects.

4.2.2.3 Previous Occurrences

The plan must present the history of hazard events. This information helps the planning team understand what has happened. While the past cannot predict the future, especially as climate change is causing more frequent and intense events, it can give an idea of what might happen and what is at risk. At a minimum, plan updates must document any state or federal disaster declarations in the last 5 years.

Previous occurrences are often presented in a table or on a map, but they can also be a narrative. Narratives of significant events, however the planning area defines them, can give the risk assessment more context. They can help participants develop problem statements and identify actions to mitigate the risk. There are many possible data sources to help you describe previous occurrences:

- Download weather-related events from the National Climatic Data Center Storm Events Database.

- Refer to the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) for previous earthquakes, landslides, wildfires and volcanoes.

- Consult the National Hurricane Center for hurricane event data.

- Contact your SHMO for more data sources and information on state disasters.

- Use the OpenFEMA data to gather disaster declarations.

4.2.2.4 Probability of Future Events

The probability of future hazard events describes how likely a hazard is to occur or reoccur. The plan must consider how future conditions will change the probability of events. Future conditions are more than just weather. Many things in the future might change the type, location, severity and frequency of hazards. Future conditions include changes in climate, population patterns and how land is used. Changes in weather patterns, average temperatures and sea levels can bring more extreme storms, droughts, wildfires and other disasters. Population changes mean changes in demographic trends, migration, density or the makeup of socially vulnerable populations. How your community uses and develops land can put more or fewer people, businesses and homes in harm’s way. These changes can all bring changes in risk and vulnerability. Investments in mitigation will reduce those risks.

Future conditions will affect different hazards differently. The Guide specifies that probability must consider how changing future conditions will affect the type, location and range of intensities of each hazard. Ask yourself:

- Will changing future conditions lead to new hazards?

- Will changing future conditions cause hazards to affect more communities?

- Will hazards reach places or people they have not before?

- Will hazards we already face become more severe? Less severe? For example, rising temperatures may make extreme heat events longer and more deadly, but may cause milder winters with rain instead of snow storms.

Probability can be described in many ways. Potential approaches include:

- Using climate model projections. Whether you use regional data or specifically down-scaled data, using projections is the best way to account for how future variation in climate will change hazard probabilities. This method is described more below. To make decisions on the use of climate model projections, consider seeking expert advice. You could reach out to the SHMO, a state climatologist or others.

- Using statistical probabilities. Statistical probabilities often refer to events of a specific size or strength. For example, the likelihood of a flood event of a given size is defined by its chance of occurring each year. A common measurement is the 1%-annual-chance flood. However, this measurement is affected by changes in the watershed and rainfall intensity. It is important that you not simply generate a probability by dividing the number of times an event has occurred by the number of years of record. This simple math will not give you a realistic picture of future probability.

- Using qualitative or general descriptions or rankings. This should be used if there are no other available data on future probabilities. If you use this approach, define any general terms. For example, “highly likely” could be defined as occurring every 1 to 10 years. “Likely” could mean to occur every 10 to 50 years, and “unlikely” could signal intervals of over 50 years. This approach must still explain how future conditions factored into the general descriptions.

You may also want to describe any time-based probabilities, or times of the year when a hazard is more likely. For example, flooding might be more frequent in the spring because of snow melt or in late summer or fall because of hurricane season. Peak tornado season is March through June.

The exact description and method of estimating future probability may vary by hazard, but it must account for future conditions.

A level of technical understanding may be required to review and evaluate the various climate models for local use. Knowing the terms used to describe climate models may help you understand which apply best to the planning area.

- Ensembles are collections of data from more than one climate model simulation.

- Downscaling is a general name for taking large-scale information and making predictions at the local level. This should be left to experts. Downscaling national data may not produce the most accurate local information and could cause more uncertainty.

- Regional Climate Models downscaledata from the Global Climate Model (or General Circulation Model) and add topographic data with a higher resolution. This produces more refined, specific results. An example of this is the North American Regional Climate Change Assessment Program.

Regional Data Approach

Local data specific to your jurisdiction(s) may be limited. If so, consider a regional data approach. This approach uses national or regional data, reports, and models to identify quantitative changes in frequency or probability. An example of this is using the National Climate Assessment. The National Climate Assessment report presents changes in a variety of aspects of climate, such as precipitation, extreme events, and temperature. It includes changes by region of the country and by sector.

You can use regional or national data to summarize anticipated climate changes. You can also find potential changes to the characteristics of weather or hazard events. This is a higher level, large-scale approach. It may lack the more granular data results of downscaled climate projections. However, it can offer very helpful information and insights on anticipated future climate conditions.

Downscaled Approach

The downscaled approach takes data from a much wider scale and applies it locally. One example is NOAA’s Climate Explorer. This online tool allows for a much more localized analysis of an area. It provides visual data and maps for a smaller geographic area. This makes them more relevant on a local scale. Like the regional approach, this methodology uses models and forecasts to look at the nation as a whole. It also allows your community to see how local conditions are projected to change over the coming decades. Another excellent source of information and resources is the web-based U.S. Climate Resilience Toolkit. This offers information from across the federal government in one location. Some states have better online mapping viewers with official climate data, and more are being developed. Those should be used for local plans. Some of these are even integrated with state GIS data layers. This makes them even more useful for mitigation planning.

4.2.2.5 Displaying Hazard Information

When developing or updating a mitigation plan, hazard-specific maps are helpful for showing hazard information, though they are not required. In some cases, a detailed narrative of potential impacts and extents can accurately convey the information you need. If your community or special district is not able to take on some technical processes, use a narrative approach. You can also address this potential gap in capability as a mitigation action later in the plan. If you use a narrative, be sure to convey all the necessary information accurately and at the right level of detail. Think of it as building a verbal map.

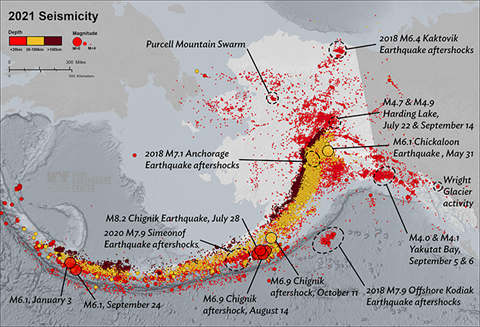

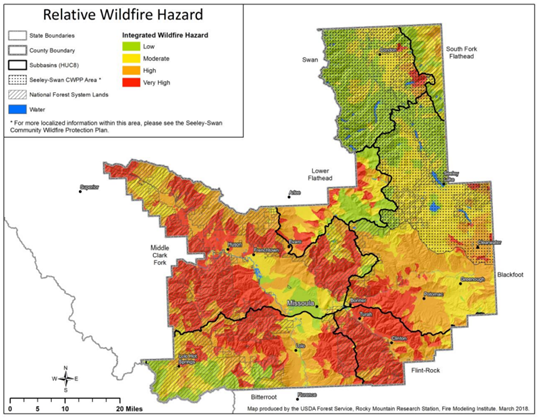

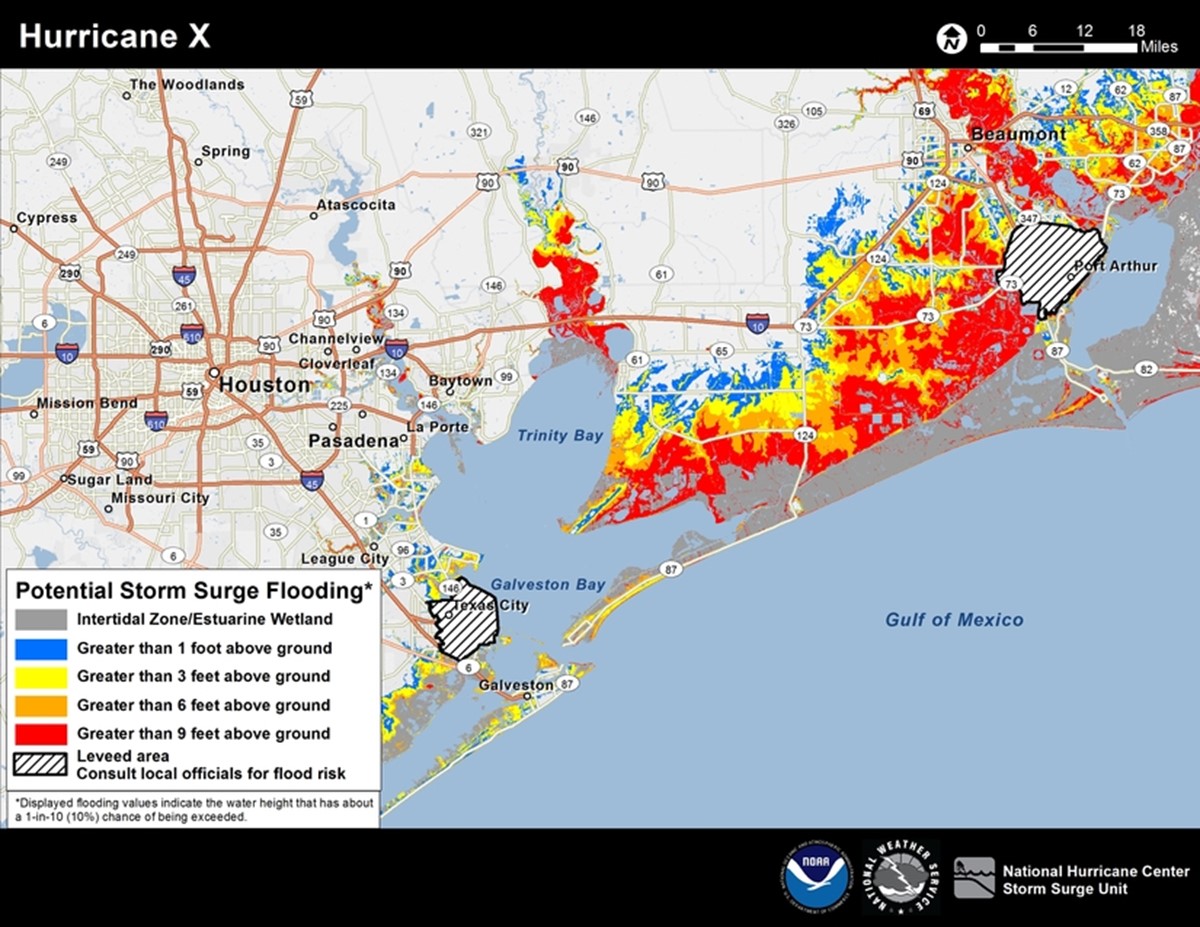

Some communities choose to use GIS or other mapping programs to display hazard and risk information. The following figures show some ways to use maps to describe the location, extent, previous occurrences and probability of future events. This applies to various hazards. Note that one map can be used to describe several hazard features. A table or matrix can help summarize the information in the hazard descriptions. It can also help identify the planning area’s most significant hazards.

Source: Missoula County/Community Assistance Planning for Wildfire Program. (Access the full-sized image)

Maps can also show the relationship between people and hazards. For example, you can create maps that show facilities that house dependent populations. Maps can identify venues that host large numbers of people. Maps can also show where socially vulnerable populations and underserved communities are. These will help show how vulnerable populations may be affected by hazards. See Figure 8 for an example of how to map the relationship between hazards and populations.

4.2.3. Identify Assets

In this next step, each participating jurisdiction identifies its assets at risk to hazards. Assets are defined broadly. They include anything that is important to the character and function of a community. They generally fall into a few categories:

- People, including underserved communities and socially vulnerable populations.

- Structures, including new and existing buildings.

- Community lifelines and other critical facilities.

- Natural, historic and cultural resources.

- The economy and other activities that have value to the community.

All assets may be affected by hazards, but some are more vulnerable. This may come from their physical characteristics or uses. An asset inventory identifies the vulnerable assets in your community. If your plan is an update, review and update the asset inventory as needed. This ensures it reflects the current conditions.

4.2.3.1 People

People are your community’s most important asset. Your mitigation plan should assess risks to people and set strategies to protect them. For the purposes of a risk assessment, think about areas of population density and groups with unique vulnerabilities. Use the risk assessment to point out areas where people are less able to prepare, respond and/or recover before, during and after a disaster. This includes underserved and socially vulnerable populations. At this stage of the risk assessment, you are identifying where people live, work and visit. To do this:

- Note any concentrations of residents and businesses.

- Note any concentrations of underserved groups and socially vulnerable populations.

- Consider development in areas of projected population growth. Predict areas of vulnerability.

- Identify places that provide health or social services that are critical to disaster recovery.

- Identify the types of visiting populations and where they may be. Visiting populations include students, second homeowners, migrant farm workers and visitors for special events. Visiting populations may be less familiar with the local area and its hazards and will be less prepared to protect themselves during an event. Assess potential problems.

A risk assessment must analyze the vulnerability of the population. To do this, it is essential to include impacts to socially vulnerable populations and underserved communities. The most at-risk members in a community tend to suffer the greatest losses from disasters. Often, they are left out of planning activities. They may have little access to information about what to do before or after a hazard event.

People from these groups may not be able to access the standard resources offered in emergencies. Consider where to locate facilities and support services for them. Think about hospitals, dependent care facilities, oxygen delivery and accessible transportation.

Several data sources and indices can help you find and learn about socially vulnerable populations or underserved communities. The CDC’s Social Vulnerability Index is a standalone resource. The Climate and Environmental Justice Screening Tool helps to find disadvantaged communities that face burdens and obstacles to resilience. The National Risk Index is a tool that identifies communities most at risk to 18 natural hazards. Other data sources are the U.S. Census, state population estimates, and the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

A jurisdiction can choose any dataset that adequately represents its socially vulnerable and underserved communities. It can also create or use a more specific dataset. Work with the rest of the planning team to find partners who represent underserved and socially vulnerable communities. They can help make sure the data fully reflect ways these populations can mitigate their risks.

4.2.3.2 Structures

Identifying structures helps you understand what existing buildings and infrastructure may be in harm’s way during a hazard event. Areas of future growth and development are also important for assessing the building environment because the planning area will experience some land use change over the 5 years the plan is approved. When identifying structural assets:

- Identify the types of buildings in the planning area (commercial, industrial, residential, etc.).

- Consider their age, construction type and whether any are critical facilities (see Section 4.2.3.3.). These factors can help you understand structural risk, including whether a building follows a disaster-resistant building code.

Existing Structures

All structures are exposed to some level of risk, where certain buildings or concentrations of buildings are more vulnerable. This can relate to their location, age, construction type, condition or use. Structure information usually comes from the local tax assessor or planning department. Find information on land use, zoning, parcel boundaries and ownership, and types and numbers of structures. In the absence of available local data, a national dataset of building locations is available from the USGS. These data will not be detailed, but will, at a minimum, show the location of buildings in your planning area. You do not need to include a list of every structure in your plan. Summarize the data to help you analyze vulnerabilities and impacts later. Often, this means summarizing the number of structures by type and jurisdiction.

Future Development

The mitigation plan is updated every five years, which does not mean that it’s a 5-year strategy. The plan should have a long-term vision to reduce risk, so it is important to think about both the structures that already exist and what might be built in the future. You won’t know exactly which buildings will be built in which locations. However, the plan should provide a general description of land uses, identified growth areas, development trends and demographic changes. This positions mitigation options to be considered in future land use decisions. Local comprehensive or master plans may have information on future land use and build-out scenarios.

4.2.3.3 Community Lifelines and Other Critical Facilities

Beyond just buildings, identify the community lifelines and other critical facilities that are critical for life safety and the economy. The operation of these lifelines and facilities during and after a disaster is crucial. Their ability to keep functioning affects both the severity of the impacts and the speed of recovery. When possible, list their construction standards, age and life expectancy or other factors that will increase or decrease their vulnerability.

Community Lifelines

As described in Task 2, community lifelines are the fundamental services in a community. The National Response Framework identifies seven lifelines. When they function, all other aspects of society can function. They are critical for maintaining public health, safety and economic viability.

Lifelines were developed to support response planning and operations, but the concept can be applied to the entire emergency management cycle, including mitigation. FEMA supports efforts to protect lifelines and to prevent and mitigate potential impacts to them. It also encourages building back stronger and smarter during recovery. All of these actions drive the overall resilience of your planning area. Work with your local emergency management agency and the state emergency management agency to identify and gather data on community lifelines.

Other Critical Facilities

You may want to identify and plan for critical facilities that fall outside of the community lifelines framework. Doing so will reduce the severity of the impacts and accelerate recovery. When possible, note both their structural integrity and content value. What are the effects of interrupting their services? It is a good idea to include a table or series of tables in the plan that describes community assets. Include elements that describe each facility, such as:

- Name.

- Type.

- Location.

- Age.

- Structure type.

- Value.

- Backup Power/Generator Capability.

Critical facilities often work together to serve the community. Think about how they are dependent on each other to see how the identified hazards may impact the facilities. FEMA understands that because these facilities are critical, you may not want to tell everyone where they are located or their potential vulnerabilities. While the mitigation plan is a public document, you can store sensitive information in sections or appendices marked as “For Official Use Only (FOUO).”

4.2.3.4 Natural, Historic and Cultural Resources

Natural Resources

Environmental and natural resources add to a community’s identity and quality of life. They also help the local economy through agriculture, tourism and recreation. They support ecosystem services, such as clean air and water. Conserving the environment may help people mitigate risk. It can also protect sensitive habitats, develop parks and trails, and build the economy.

The natural environment can also protect residents by reducing the impacts of hazards and increasing resiliency. Examples of this include:

- Wetlands and riparian areas absorb floodwater.

- Soil and landscaping are used to manage stormwater.

- Plantings control erosion, reduce runoff and can create shade to protect from extreme heat.

Don’t forget to consider natural resources, not just the built environment, as you identify assets.

Historic Resources

Historic resources tell the story of your community. Historic properties may be a (1) site, like a battlefield or shipwreck; (2) building, like a house or barn; (3) structure, like a lighthouse or bridge; (4) an object, like a fountain or monument; or (5) district, which shares a significant identity and continuity among either its sites, buildings, structures, or objects that are united historically, like a business district. In the United States, the National Historic Preservation Act, and its regulations, help the nation identify and manage its historic properties. In addition to the nationally significant historic properties on the National Register of Historic Places, a state or local community may have its own register. Historic properties offer a myriad of social and economic benefits. Your community should work to identify these important resources to protect from natural hazards.

Cultural Resources

The inventory should list assets of the local culture that are unique or cannot be replaced. Museums, geological sites, concert halls, parks and stadiums can qualify. Review state and national historic registries to identify the cultural assets that are significant to the community.

4.2.3.5 The Economy

After a disaster, economic resiliency is one of the major drivers of a speedy recovery. Each community has specific economic drivers. Considering these as you plan can reduce the impacts of a hazard or disaster on the local economy. Economic assets can have direct or indirect losses. For example, building or inventory damage is a direct loss. Functional downtime and loss of wages are indirect losses. These are losses you can calculate. Know the primary economic sectors in the community. These may include manufacturing, agricultural or service sectors. Major employers and commercial centers are also a factor. Also consider workforce housing and day care needs.

4.2.3.6 Activities that Have Value to the Community

What activities are important to a community? Does it have long-standing traditions, such as a festival or fair? Some areas rely on seasonal industries to sustain them throughout the year. A hazard event that cancels or shortens these can affect a community’s livelihood.

Tourism and farming are two examples of seasonal activities. They typically have lulls during the winter months in warmer climates, while tourism may pick up in colder regions. Extended severe weather, happening earlier or later in the season than normal, can severely impact the local economy.

4.2.3.7 Update to Reflect Changes in Development

Plan updates must describe any development that took place since the last plan was approved. The planning team can get this information from planning and building departments. These data can help you evaluate whether the vulnerability has increased, decreased or remained the same. If planned development is in identified hazard areas or is not built to updated building codes, it may increase your community’s vulnerability to future hazards and disasters. If development occurred with mitigation in place, vulnerability may have remained the same. Development could also reduce risk. For example, a new fire station could be built to replace one that was not seismically sound or was in a high-hazard area.

The planning team shall also consider other conditions. Climate change, changing populations, infrastructure expansion or economic shifts can affect vulnerability. Perhaps no significant changes occurred. Maybe they did not affect the jurisdiction’s overall vulnerability. In that case, you can validate the information in the previous plan. Make sure to account for shifting demographics, including those relevant to socially vulnerable populations and underserved groups.

4.2.4. Analyze Impacts

After you identify the hazards and assets, you can analyze the impacts. To do so, you will look at the risks (where hazards overlap with assets), describe asset vulnerabilities, and describe the potential impacts. Impacts may include loss estimates for each hazard. This helps the community see the planning area’s greatest risks.

The plan must describe how each profiled hazard can affect the identified assets. The type and severity of impacts reflect both the magnitude of the hazard and the vulnerability of the asset. Impacts are also affected by the community’s ability to mitigate, prepare for, respond to and recover from an event. You can describe impacts in many ways. They can be physical (damage), monetary (estimated building or economic losses) or social (disrupted community life). Impacts must include the effects of future conditions, including population, land use, development and climate change.

Not all hazard events create an impact on their own. One event can lead directly to another. These are called cascading hazards. Plans should consider how hazards can cascade. An example of this is the increased flood and landslide risk after wildfires. Or, a dam or levee may fail upstream and cause downstream flooding. Cascading events may begin in a small area. They can intensify and spread to affect larger areas. Evaluate how the natural hazards affect a local community. This is a vital piece of the hazard analysis in a local mitigation plan.

4.2.4.1 Methods to Analyze Impacts

There are three ways to analyze impacts:

- Start with the past. Explain impacts by looking at historic impacts and losses from similar events. Describe what may happen in the future based on these past events. This is called historical analysis.

- Overlay assets and hazards. This is called exposure analysis. It is usually done with maps and GIS software.

- Ask yourself “what if?” This is scenario analysis. It uses hypothetical scenarios to describe impacts. This can be helpful for events that do not have a defined hazard area or do not happen often.

No matter the method, you can describe impacts qualitatively or quantitatively. A qualitative analysis may describe the types of impacts. To do this, gather a team to brainstorm and discuss potential impacts. Include the planning team, subject matter experts, stakeholders and members of the community. A quantitative evaluation assigns values and measures the potential losses to the assets.

Historical Analysis

Historical analysis uses data on the impacts and losses of previous hazard events. These help predict the impacts and losses for a similar future event. This can be especially useful for weather-related hazards, such as severe winter storms, hail and drought. These events are frequent, so communities are more likely to know about them. Communities may have data on their impacts and losses. For recent events, don’t simply consider what was damaged. Think about what might have been damaged if the event had a greater magnitude. For hazards with no recent events, consider the new development and infrastructure that would be vulnerable.

Use historical analysis to indicate future events when there is no other data available. For example, an event that has occurred 20 times over the past 50 years has a 40-percent annual probability. This data should be used with caution because current trends indicate that the type, frequency, and magnitude of hazard events will change as the climate continues to change. It may not give you a realistic understanding of future probability. Research and data on future climate and weather patterns is advancing quickly, so it is okay if you do not have detailed climate data for your plan right now. Identify where there are gaps in the data and include filling those gaps in the mitigation strategy.

Exposure Analysis

An exposure analysis identifies the existing and future assets in known hazard areas. GIS is often used for this analysis and to make maps to visualize the risk. You can also consider the magnitude of the hazard. You may identify which assets are in areas of high, medium or low wildfire hazard, or in areas of different flood frequencies (1%- or 0.2%-annual-chance flood risk).

An exposure analysis can quantify the number, type and value of structures, community lifelines and other assets in areas of identified hazards. It can identify any assets exposed to multiple hazards. Exposure analysis can also help you understand areas that may be vulnerable if and when buildings, infrastructure and community lifelines are built in hazard-prone areas.

It can be a challenge to describe the exposure of assets to more than one hazard. Maps are a good tool for this task. A map can show at a glance that an asset is exposed to multiple threats. Figure 11 includes the location of floods, wildfires, dam failures, railroad accidents and a hazardous materials incident. It also points out where development is anticipated (new subdivisions, public facilities and commercial redevelopment). It shows future annexation areas as well.

Scenario Analysis

A scenario analysis asks "what if" a certain event occurs. This kind of analysis uses a hypothetical situation to think through potential impacts and losses. A scenario analysis can be done narratively by walking through a scenario with the planning team and documenting what could happen. It can also be done using GIS modeling.

FEMA’s Hazus program is one of the most common scenario analysis tools for hazard mitigation. Hazus provides standardized tools and data to estimate risk from earthquakes, floods, hurricanes and tsunamis. Each model uses data on buildings, infrastructure and population together with hazard data and damage functions to model impacts. The impacts Hazus models vary by hazard. For more information on what results Hazus creates and how the software works, review the User and Technical Manuals and the Hazus trainings on FEMA’s YouTube channel.

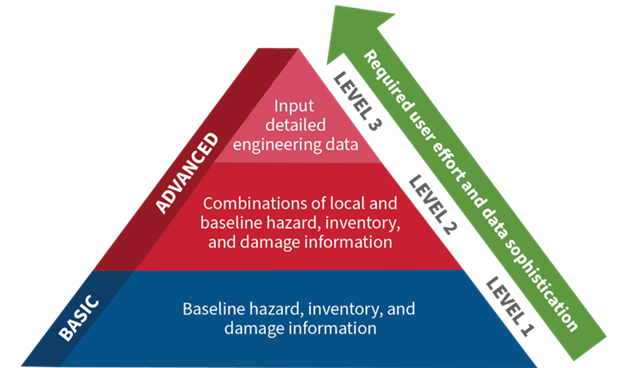

Hazus can be used “out of the box” with no modification. This basic (“Level 1”) Hazus analysis produces results based on the national databases in the Hazus software. Level 1 analysis results generally take less time and expertise to generate. You can also check the Hazus Loss Library to see if there is an existing Hazus analysis for your planning area.

Users can modify all Hazus model inputs to include more refined information. Adding local data makes the output more accurate and specific to your planning area. This is called an advanced (Level 2 or 3) analysis. Level 2 and 3 analyses bring in local asset information and more detailed engineering data (see Figure 12).

If you want to refine your analysis but do not know where to start, many professionals can help. Geologists and hydrologists can improve your hazard data. GIS professionals can replace baseline inventories with local asset information. Engineers could improve the baseline building vulnerability parameters and damage functions.

Combining Available Data and Methods

Many plans combine methods to analyze impacts. The combination of methods will depend on the hazard. It may also depend on the available time, data, staff and technical resources. For instance, analyzing flood risk could include the following:

- Public assistance costs and insured and uninsured losses.

- Finding the number and value of community assets in flood hazard areas. Noting any specific vulnerability due to physical features or common uses.

- Estimating the physical, economic and social impacts of a 1%-annual-chance flood event, based on a Hazus model.

- Using the current zone maps to describe any future development that may be at risk of flooding.

There are many ways to analyze the data and show the results. But the analysis step should result in a description of the potential impacts of each hazard on the assets of each jurisdiction. You may use factors like annualized losses in a table to illustrate the impacts. Components that affect annual losses could include:

- Location.

- Structural damage.

- Non-structural damage.

- Contents damage.

- Total estimated losses.

These analyses can generate a lot of data. Use tables to summarize the exposed assets. You may want to include the number, type and total value of all assets in hazard areas.

Once the jurisdiction assembles data on its socially vulnerable populations and underserved communities, it can be helpful to map the data and see where they overlap with known and possible hazard areas. Socially vulnerable populations and underserved communities often do not have access to the resources they need to become more resilient. Identify where they live, work and shop in relation to hazards. Prioritize future outreach and investments to reduce risk based on these findings.

Finding the areas where people are most vulnerable to hazards goes beyond a GIS overlay. Some measures of social vulnerability or disadvantage cannot be mapped. To understand the most vulnerable populations, look at how government policies and programs affect them. For example, discriminatory housing policies may have pushed low-income people and communities of color onto land with the least value and highest risk. Communities may be more exposed to the impacts of hazards because they do not have the funds or the manpower to reduce their risk. Evaluate the impacts of historic and current policies, programs and decisions that have caused disproportionate harm to underserved groups and socially vulnerable populations. Propose specific actions to increase resilience for those groups.

This analysis will help you create a more equitable mitigation strategy that supports underserved groups and socially vulnerable populations in achieving a more resilient future. It also equips you to reduce the risk of the people most affected. Use its results to identify actions that build resilience for these groups.

4.2.4.2 Impacts Related to Climate Change

The Guide specifies that the mitigation plan must discuss the impacts of climate change in the risk assessment. You may have already discussed the effects of climate change on hazards in the profile discussions for each hazard. The impact section is another area where it is valuable to discuss climate change. The Climate Mapping for Resilience and Adaptation website has detailed information on this topic. Use it to find how climate change may affect your jurisdiction(s). Look at how climate change may shift your community’s hazard exposure over time. This can guide your long-term planning for hazard mitigation. It can also help you identify areas where socially vulnerable populations and underserved communities might face a greater hazard exposure. This can help you target mitigation projects where they are needed most.

A plan’s strategy section should look at the changing conditions that can impact the planning area. This means it has to look at the risks the local jurisdiction faces now and those it will likely see in the future. Those may include the impacts of climate change and other future conditions, such as changing demographics or population patterns and development trends. Localities may also need to find new mitigation actions to reflect new risks, capabilities or goals. These new factors may include changing conditions, such as climate or demographic changes, that can affect social vulnerability. One key factor to remember is that new community members are not as familiar with local hazards. Your planning process should reflect this throughout to decrease vulnerabilities in your community.

4.2.4.3 Include Repetitive and Severe Repetitive Loss Properties

The plan must address repetitively flooded, NFIP-insured structures. This includes both repetitive and severe repetitive loss properties. Identify areas of repetitive damage that Public Assistance funding could be used for mitigation in future federally declared disasters.

Table 7: Repetitive and Severe Repetitive Loss Definitions

| Type | Definition |

|---|---|

| Repetitive Loss Properties | A structure covered by an NFIP flood insurance policy that: |

| • Has had flood-related damage on two occasions, with the average cost of repair at or over 25% of the value of the structure at that time; and | |

| • When the second flood-related damage took place, the policy had Increased Cost of Compliance coverage. | |

| Severe Repetitive Loss Properties | A structure covered by an NFIP flood insurance policy that has had flood-related damage: |

| • For which four or more separate claims payments for flood-related damage have been made. The amount of each claim (including building and contents payments) exceeded $5,000, and the cumulative amount of the claims payments exceeded $20,000; or | |

| • For which at least two flood insurance claims payments (building payments only) have been made, with a cumulative claims total that exceeds the market value of the insured structure. |

The Risk Assessment must estimate the numbers and types of these properties. The types are residential, commercial, institutional, etc. Contact your state NFIP coordinator or local floodplain administrator for how to obtain that information.

In addition to repetitive and severe repetitive loss properties, there are other factors of High-Risk Properties. These are properties that are more at risk to flooding. Some of the factors that make these properties good candidates for mitigation include those that:

- Have been substantially damaged,

- Are close to a flood source,

- Receive FEMA Individual Assistance,

- Have shown flood damage through state or local inspection, or

- Are at high risk according to sources like:

- Elevation certificates,

- Regulatory products like FISs or FIRMs, or

- Hydrologic and hydraulic studies.

An example of a High-Risk Property is one where the elevation certificate shows that the lowest floor is below the Base Flood Elevation (BFE). The BFE is established by the FIRM. This means the property is at risk to both the base flood as well more frequent events.

4.2.5. Summarize Vulnerability

Vulnerability is being at risk from the effects of hazards. The term applies to assets such as structures, systems and populations. A community may define other assets in areas known to be hazardous.

The previous steps in the risk assessment create a great deal of information on hazards, vulnerable assets and potential impacts and losses. The planning team shall summarize this information to help the community understand its most significant risks and vulnerabilities. The summary of vulnerabilities then informs the mitigation strategy. It will also help you share the data with elected officials and others in a condensed and accessible format, better allowing them to make informed decisions for the community.

One good approach to summarizing vulnerabilities is to write problem statements. For instance, your analysis of impacts and losses helps you see which critical facilities are in hazard areas. You know which neighborhood had the most flood damage in the past. You know which hazard-prone areas are zoned for future development. Select the information on the issues of greatest concern. The planning team can see the impacts of each hazard. This will help them develop problem statements (see below). They may also identify problems or issues that apply to all hazards.

When you are developing a plan, revise the problem statements to reflect the current risk assessment. You may need to develop new statements. Remove or revise ones that are no longer valid. Perhaps mitigation projects have addressed the risk or conditions have changed.

Here are some example problem statements:

- The sewage treatment plant is in the 100-year floodplain. It has been damaged by past flood events. It serves 10,000 residential and commercial properties.

- The city recently annexed an area in the wildland-urban interface. The land use and building codes do not address wildfire hazard areas. Future development in the wildland-urban interface will increase the vulnerability to wildfires.

- The city is in a seismic hazard area and is subject to severe ground shaking and soil liquefaction. Hazus predicts a 6.0 magnitude event would result in $10.5 million in structural losses and $40 million in non-structural losses. Damage will be greatest to the 100 unreinforced masonry buildings (pre- building code) in the downtown business district.

- The schools are a central focus of the community. They offer opportunities to educate the public about hazards, risk and mitigation. In addition, many school facilities are vulnerable to one or more hazards, including flooding, earthquake, tornado and severe winter storms.

- Within the city, people of color and lower-income families are concentrated in high-density urban areas that receive a disproportionate exposure to extreme heat events.

- Evacuation route signs are only provided in English. The city has a large number of non-English speaking residents who therefore may not be able to access evacuation routes in a disaster.

- The city is in a coastal area that is subject to the effects of sea level rise. Climate change is causing sea levels to rise, which is causing coastal inundation that threatens over 250 residential properties.