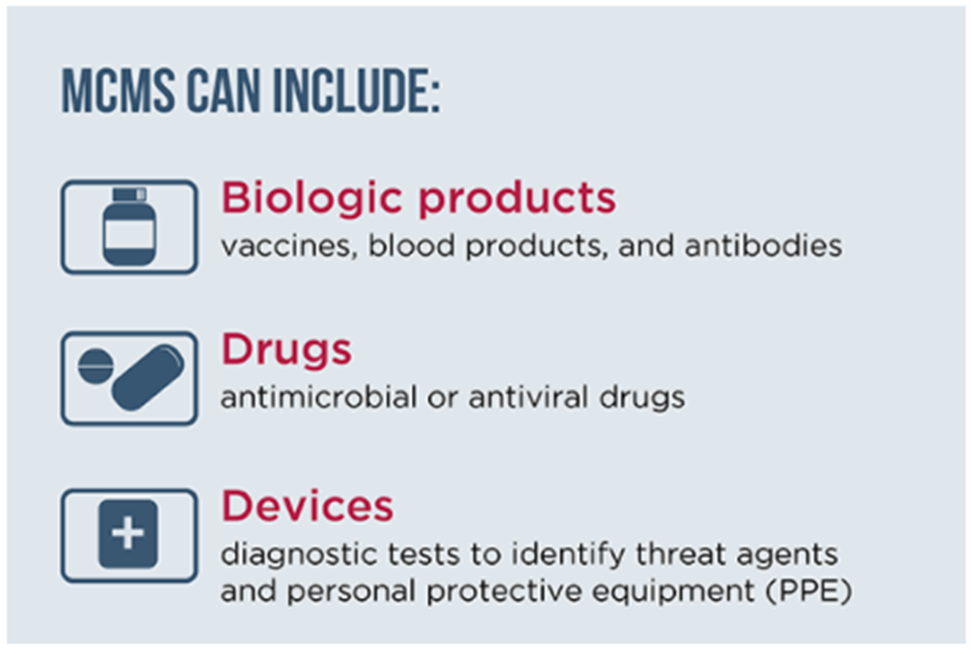

Once the cause of disease is known, MCMs that effectively treat or prevent the disease can be utilized, if available. Effective use of MCMs during a biological incident will not only help reduce the spread of disease but also reduce incidences of illness, thus reducing the burden on healthcare systems; often, MCMs will be paired with NPIs. MCMs include materials used to prevent, mitigate, or treat adverse health effects, such as PrEP/PEP and therapeutics, diagnostic tests, and PPE. MCMs, such as antibiotics, antitoxins, vaccines, and antiviral drugs, can be used to treat patients with disease symptoms or to prevent and/or slow the development of disease in exposed or potentially exposed individuals. Prophylaxis may also be provided to individuals who are at high risk of being exposed during the response (e.g., first responders, human and veterinary healthcare providers, etc.) or those who were exposed but have yet to develop illness symptoms. PPE such as protective clothing (e.g., gloves, gowns, etc.), eye protection (e.g., face shields or goggles), and masks or respiratory protection (e.g., disposable filtering facepiece respirators and positive air purifying respirators) are additional examples of MCMs that may be employed during a biological incident. The type of PPE employed will depend on the characteristics of the biological agent involved (i.e., pathogens transmitted through inhalation versus environmental contact or other exposures).

3.2.1 Access to Medical Countermeasures

State and local caches and hospital supplies can serve as sources of readily deployable MCMs that can be accessed quickly during emergencies. Hospital supplies may be available for immediate use while waiting for the arrival of supplies from other sources, but inventory generally is limited. Hospitals do not typically stock MCMs that are seldomly used (e.g., smallpox vaccines) and rarely have on hand more than a few weeks’ supply of an MCM that would be used during the course of normal operations. Therefore, even if an MCM is available in a hospital (e.g., broad spectrum antibiotics), existing supplies alone would be insufficient to treat a surge of patients during a major, prolonged biological incident.

States and localities may maintain their own MCM stockpiles, which may be forward-deployed within or near planned MCM dispensing sites.55 Depending on the size and scope of a biological incident, the Strategic National Stockpile (SNS), managed by HHS ASPR, may be activated to provide speedy access to additional/alternative MCMs. Achieving efficient delivery of MCMs from storage sites to areas in need and then dispensing them to affected individuals requires carefully and comprehensively designed dispensing plans. Within the SNS, materials may be tracked by local and state public health leaders on the Inventory Management and Tracking System (IMATS). When thousands of people need MCMs quickly, dispensing of SNS and state/local MCM caches, such as vaccines, antibiotics, and PPE, to affected populations will likely occur through Points of Dispensing (PODs), which are pre-identified sites planned to serve the dispensing needs of specific areas or populations. Considerations for the utilization of PODs during a biological incident are discussed in the callout box that follows.

Points of Dispensing (PODs)

A POD is a community location where state and local agencies dispense MCMs to the public during a public health emergency. A system of PODs should be tailored to the specifics of the event, including the transmissibility of the pathogen, the uncertainty of the population at risk, and contamination caused by the incident, which will influence the location of the PODs and their number, layout, throughput, and extensive staffing needs. Additional considerations include ensuring the safety and security of the POD site, its staff, and the public. For intentional incidents, the threat of a follow-on attack at a POD location should be considered.

Ensuring that the facility temporarily housing the POD can return to its normal use is critical for recovery. This goal can be accomplished by planning for site clean-up, decontamination, and disposal of unused MCMs (or return to the SNS) and un-recoverable equipment. Medical care for staff who may become exposed while performing their duties also must be considered. Readers are directed to section 5.2 Medical Countermeasures Use in Healthcare Facilities for further discussion of closed PODs providing MCMs for hospital staff and patients.

What Will You Need to Know?

- How will you coordinate with public health and HCCs to know if there are appropriate MCMs and sufficient supplies of MCMs in your jurisdiction?

- How does the jurisdiction plan to track MCMs supply and burn rate? How will it work with private sector partners to accomplish MCM tracking?

- How does the jurisdiction plan to adjudicate/prioritize resource assistance requests, determining those based on real need versus perceived need?

- What will you do if there is a shortage or appropriate MCMs are unavailable?

- What do state and local caches of MCMs contain, and where are they located? How can these caches be accessed?

- Who will you contact in your region to coordinate distribution of regional resources?

- What are the plans for SNS distribution in your state? In your region/locality?

- How can emergency management personnel or assets support MCM sites (e.g., PODs, testing centers, or vaccines clinics)?

- What will be the role of volunteers in PODs, such as Community Emergency Response Teams (CERTs), Medical Reserve Corps, and American Red Cross?

- What sites are designated POD locations in your area?

- Are they accessible to vulnerable populations and underserved communities?

- How will you coordinate with animal health officials to know if veterinary MCMs are needed and available for household pets and service animals?

- How will you coordinate with public health, HCCs, and laboratories to know about the status of diagnostic testing capacity for your community?

- If labs are experiencing workforce shortages, supply shortages, or testing turnaround times are delayed, how will you know?

3.2.2 Plan for Medical Countermeasure Challenges

MCM use in a biological incident is not without challenges. For example, because many MCMs treat or prevent only one disease (such as most vaccines), the identity of the pathogen causing the outbreak must be known before some types of MCMs may be deployed. Additionally, the infectious agent may be intentionally (or, in some cases, naturally) altered to be resistant to available treatments, making the resulting disease more difficult to treat or untreatable with available MCMs. Alternatively, specific MCMs may not be available for the pathogen involved (e.g., a toxin or an emerging agent).

Limited capacity for pathogen-specific diagnostic testing in public health laboratories (state and federal) and in independent, hospital, or academic clinical laboratories can present significant challenges to surge testing during a widescale biological outbreak. Staffing shortages, limited access to supplies, and increased demand for testing can all contribute to increased turnaround times and slower test results. The type of testing sample (e.g., nasal swab or blood test) may require additional considerations for both sample collection and test site set up. Moreover, limitations in the availability and accessibility of community testing sites can hinder public health officials’ ability to track local infection trends. These challenges in diagnostic testing can impede efforts to control disease spread and may be exacerbated during major communicable disease outbreaks.

Not all biological incidents will require community-wide testing campaigns to control the spread of disease, such as incidents resulting from contaminated water or incidents involving non-contagious pathogens. When such campaigns are beneficial for controlling disease spread, their effectiveness will depend on the public’s willingness and ability to participate in testing. Further, the public’s willingness to comply with directives that hinge upon testing results (such as self-isolation or quarantine) will impact efforts to control disease spread. Perceived social stigma and potential threats to employment from positive results also can adversely affect compliance. Failure to provide clear and consistent messaging, coupled with the threat of individual social and economic impacts, can derail community-wide testing campaigns. (Refer to KPF 2: Communicate with External Partners and the Public, for messaging strategies that will promote the public’s confidence in the information they receive and their compliance with appropriate directives.)