4.1 Rail Tank Car Rupture

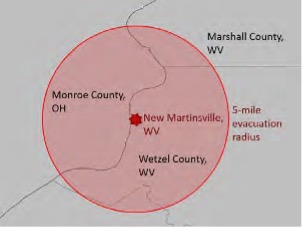

On the morning of August 27, 2016, a rail tank car freshly loaded with nearly 180,000 pounds of liquified chlorine ruptured in New Martinsville, WV.12 Over the next 2.5 hours, the entire load was released into the air as yellow-green chlorine vapor and migrated with the wind south along the Ohio River valley.

Employees immediately initiated a chlorine release alarm and the facility area was evacuated. Incident command posts were activated for Marshall and Wetzel counties, WV, and Monroe County, OH. Nearly two thousand households spread over three counties located within a 5-mile radius of the facility were ordered to evacuate. Adjacent industrial facilities activated shelter-in-place procedures. Traffic was halted on nearby state routes and rail lines, and the US Coast Guard halted commercial river traffic on the Ohio River. Because response plans were in place, officials in the area were able to rapidly implement response activities appropriate to the release event, and successfully protected area populations.

The incident resolved quickly because liquid chlorine evaporates quickly and the resulting vapor cloud dissipated within a matter of hours. Community evacuations were lifted late that afternoon, after the WV Department of Environmental Protection (WV DEP) Homeland Security and Environmental Response Group (HSER) found no detectable chlorine at several nearby locations.

4.2 Train Derailment

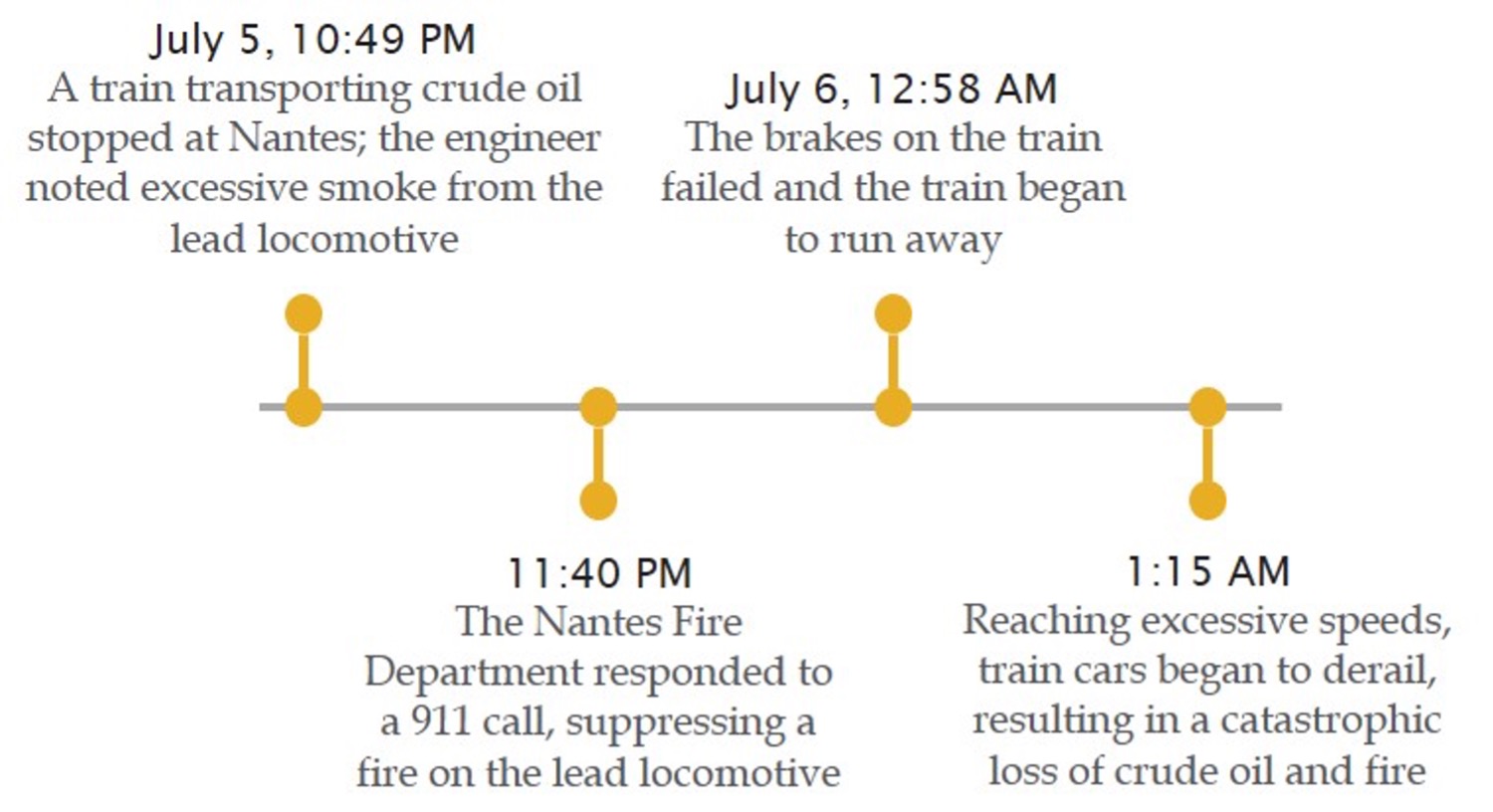

During the early morning hours of July 6, 2013, the citizens of Lac-Mégantic, Quebec were awakened by fires and explosions caused by the derailment of 63 train tank cars carrying petroleum crude oil. The incident destroyed 40 buildings and claimed 47 lives. Two thousand people were evacuated.13

The day before, the lead locomotive of the train had been experiencing mechanical difficulties. Although smoke was coming from the lead locomotive stack, it was decided repairs could wait until the following morning. That night, the train was parked in Nantes (7.2 miles from Lac-Mégantic) on a descending grade. Overnight the train’s brakes failed and at about 1:00 AM the train started to roll downhill toward Lac-Mégantic, picking up speed as it proceeded down the grade. It passed through 13 level crossings before derailing near the center of town at a speed of 65 mph. Nearly 6 million liters of petroleum crude oil were released, causing a large fire and multiple explosions.

More than 1,000 firefighters from 80 different municipalities in Quebec and six counties in Maine participated in what was reported to be the largest fire response in recent Quebec history. Approximately 33,000 liters of foam – a quantity not available locally, but transported in from 180 km away – were applied to the fire to get it under control. In addition to the immediate danger from fire, the downtown area and an adjacent river and lake were contaminated with spilled crude oil and firefighting foam. Numerous organizations supported the response, including the Montreal, Maine & Atlantic Railway (MMA), Canadian National (CN) railway, the Railway Association of Canada (RAC), the federal and provincial governments, World Fuel services, Inc. (WFSI), the importer (Irving Oil Commercial GP), the petroleum industry, and environmental remediation companies.

Throughout the immediate accident response, regular coordination meetings were held to discuss priorities, actions and methods, and overall response progress. However, at the time of this accident, an emergency response assistance plan (ERAP), which guarantees that resources required to assist local responders during an accident will be readily available, was not required by Transport Canada’s Transportation of Dangerous Good (TDG) Regulations for petroleum crude oil. In fact, at one point during the early response to this accident, work at the site stopped for several hours due to concerns about the ability of the MMA railway to cover emergency response costs. The stoppage affected the progress of both emergency response and environmental remediation efforts – in some areas, oil migrated back into zones that had earlier been declared safe.

Through the years, recovery efforts have faced considerable challenges. The oil spilled and the ensuing fires wreaked havoc on the local environment, including the contamination of multiple water sources and the town’s soil to a depth of 3 m.14 In the years following the accident, costs for rebuilding and environmental remediation have mounted; estimates have run into the hundreds of millions if not billions of dollars.15 Even now, more than five years later, reconstruction is ongoing, and the question of who will foot the bill for the recovery efforts remains unanswered.16

Footnotes

12. National Transportation Safety Board. (2019, February 11). Hazardous Materials Accident Report: Rupture of a DOT-105 Rail Tank Car and Subsequent Chlorine Release at Axiall Corporation, New Martinsville, West Virginia, August 27, 2016. (Report No. NTSB/HZM-19/01).

13. Transportation Safety Board of Canada. (2014). Railway Investigation Report R13D0054. Runaway and main-track derailment. Montreal, Maine & Atlantic Railway, Freight train MMA-002, Mile 0.23, Sherbrooke Subdivision, Lac-Mégantic, Quebec, 06 July 2013. (Report No. R13D0054.)

14. de Santiago-Martín, A., Guesdon, G., Diaz-Sanz, J., Galvez-Cloutier, R. (2015, December 2). Oil Spill in Lac-Mégantic, Canada: Environmental Monitoring and Remediation. International Journal of Water and Wastewater Treatment. 2(1): ; Galvez-Cloutier, R. (2015, May). The human and environmental disaster at Lac Mégantic: the event, the impacts and the lessons to be learned. 14th Global Joint Seminar on Geo-Environmental Engineering. Montreal CSCE, CGS. 21-22.; Mann, Brian. (2013, October 14). National Public Radio.; CBC News. (2013, September 17). Lac-Mégantic an ‘environmental disaster,’ says expert. CBC News.

15. de Place, E. (2014, December 18). What do oil train explosions cost? And why cities and towns would have to pay the damages. Sightline Institute. ; Mikulka, J. (2015, June 21). Cost of doing business? Oil companies agree to pay for some of Lac-Megantic damages, but not to solve the real problems. DeSmog Blog.

16. Murphy, J. (2018, January 19). Lac-Megantic: The runaway train that destroyed a town. BBC News, Toronto.; Giovanetti, J. (2013, August 14). Plan to reshape Lac-Mégantic gathers momentum as town rebuilds. The Globe and Mail. ; Woods, A. (2013, July 23). Lac Megantic: Mayor says town stuck with $4 million in unpaid bills for cleanup. The Star. ; Belander, M. (2013, August 14). Quebec targets CP railway for Lac-Mégantic cleanup costs. The Canadian Press