3.1 Pesticide Exposure in Farm Workers

During the 1970s, California grape growers relied heavily on organophosphorus pesticides which were known to be toxic to humans. At the time, fieldworkers were protected from harmful exposure by restricting their access to treated fields for days (or weeks) after pesticide application. Growers who used organophosphorus compounds were required to have an emergency medical plan, including arrangements for proper medical care of workers accidentally exposed to harmful levels of pesticides.6

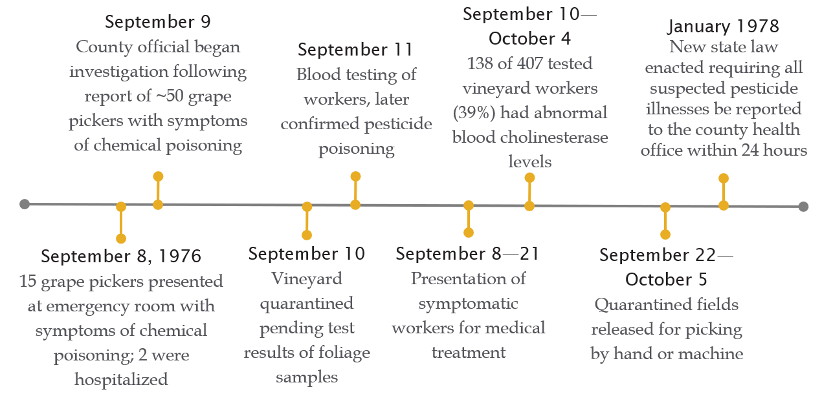

On the evening of September 9, 1976, a private physician in Madera County, CA, alerted the local health official to a potential chemical poisoning.6,7 The physician had already treated 25 field hands from a single vineyard, and now had another large group of workers, brought in by the same labor contractor, who were all suffering from nausea, vomiting, dizziness, and weakness. The health official’s call to the local community hospital emergency room confirmed that a number of fieldworkers had been treated there for similar symptoms over the past day or two as well. The health official made arrangements with the county agricultural commissioner to begin a joint investigation at the vineyard the next morning.

California Department of Food and Agriculture (CADFA) laboratory analyses of vine foliage samples from vineyard locations where the workers had been harvesting when they became ill identified high levels of dialifor (Torak®) and phosalone (Zolone®), both organophosphorus pesticides in the same class of chemical as the nerve agent sarin. Workers had apparently been allowed into recently-treated areas before the expiration of the required 30-day safety interval for dialifor, and had suffered exposures to pesticide residues through the skin. In all, 118 workers from a 120-person grape-picking crew at the vineyard became ill. Of these, 85 received medical attention and three were hospitalized.

The incident may not have been noticed and worker exposures likely would have continued without the cooperation of several state and local agriculture and health agencies including CADFA, the Environmental Protection Agency, the California Department of Health, and the California Division of Industrial Safety (CAL-OSHA), and the Madera County Agricultural Commissioner's Office. Even so, this event represents the largest known single incident of such poisoning among fieldworkers in the US. The large number of acutely ill patients severely taxed medical resources; as a result, comprehensive reporting of emergency treatment by physicians fell by the wayside.

The vineyard owner was ordered not to harvest grapes from fields containing unsafe levels of pesticide residues. He sustained significant losses while his vineyards were under quarantine and had to pay substantial medical expenses and a fine for violating state regulations concerning the proper use of pesticides.

Neither dialifor nor phosalone have been used in agriculture in the US for decades.8

3.2 Contaminated School Lunches

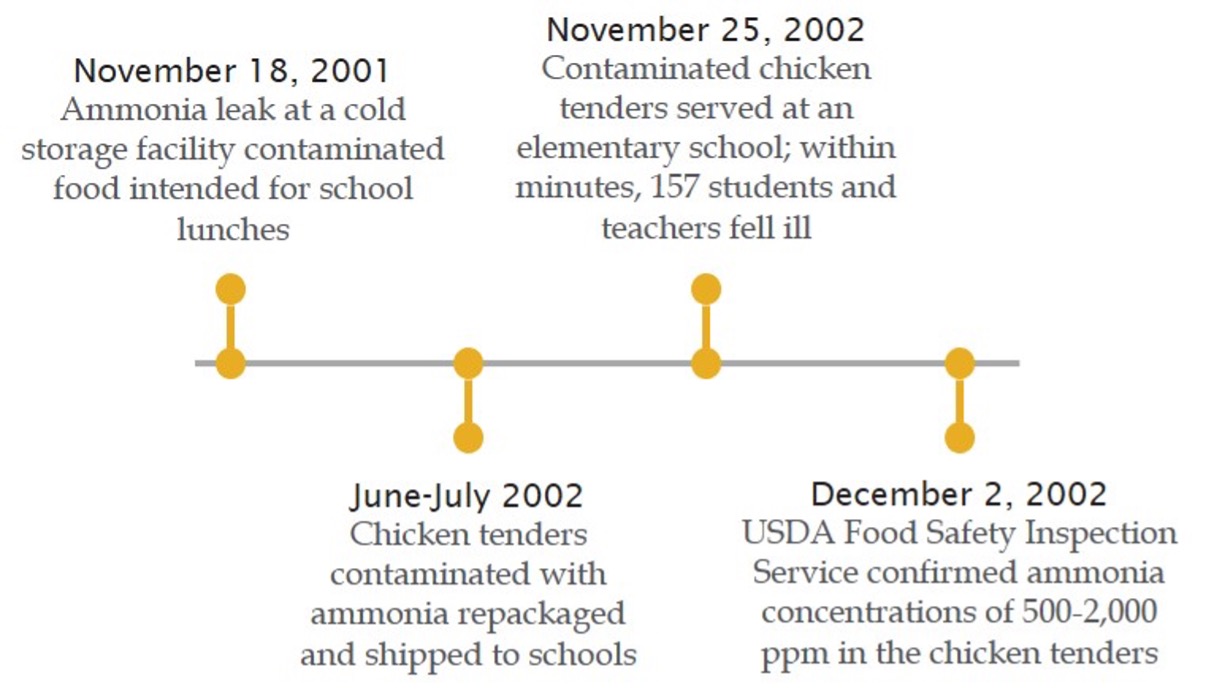

On November 25, 2002, several students eating the school lunch in Will County, Illinois, noted an ammonia-like odor in the chicken tenders, but ate them anyway. Within an hour, dozens were vomiting in school bathrooms and hallways. The school notified the county health department, which alerted the five local hospital emergency departments to the incoming 18 ambulances transporting 42 children and two adults. In all, 157 people (151 students and 6 teachers) became ill. Miraculously, no one was hospitalized, and many of the affected individuals reported feeling well within hours of onset.9

Soon after, the Illinois Department of Public Health found ammonia at levels greater than 1,000 ppm in heated chicken tenders and nearly 2,500 ppm in frozen chicken tenders from the school. Although aqueous ammonia used in food processing is “Generally Recognized as Safe” (GRAS) by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and levels are not limited, ingestion of ammonia at levels higher than normally found can cause gastrointestinal illness and damage, even death at sufficiently elevated levels, due to its caustic nature. The ammonia levels measured in the chicken tenders were well above both the usual limit of 15 ppm in food10 and the < 50 ppm ammonia odor threshold. 11 This incident illustrates the unfortunate truth that, given the right circumstances, individuals will ignore unpleasant and recognizable indicators and put themselves at risk of exposure.

An investigation revealed that the chicken had been exposed to a spill of liquid ammonia (a common refrigerant) during storage in a warehouse facility a year earlier, in November 2001. Instead of being destroyed, over 300 cases of the product were re-packaged and stored for months before being distributed to nearly 50 schools throughout Illinois. At least four other schools had noticed an ammonia smell from the chicken, and one school had served the product on October 2, 2002; luckily, no unusual illnesses were noted at these schools. After the November 2002 incident, all remaining product was destroyed.

This incident illustrates the importance of public health preparedness plans that include two-way communication between emergency and health departments. Such communications can give medical personnel valuable minutes to prepare for the arrival of large numbers of patients and review information that might allow for a more rapid diagnosis of unfamiliar conditions and preparation of an antidote, thus potentially helping save lives.

Footnotes

6. McClure, CD., Peoples, SA., & Maddy, KT. (1978). Public health concerns in the exposure of grape pickers to high pesticide residues in Madera County, Calif., September 1976. Public Health Reports, 93(5), 421-425.

7. Peoples, S. A., & Maddy, K. T. (1978). Organophosphate pesticide poisoning. The Western Journal of Medicine, 129(4), 273–277.

8. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. (1998). Status of Pesticides in Registration, Reregistration and Special Review (Rainbow Report). Office of Pesticide Programs. (Report No. EPA 738-R-98-002)

9. Dworkin, M.S., Patel, A., Fennell, M., Vollmer, M., Bailey., Bloom, J., R. et al. (2004). An outbreak of ammonia poisoning from chicken tenders served in a school lunch. Journal of Food Protection. 67(6). (pp. 1299-1302).

10. Centers for Disease Control. (1986). Ammonia contamination in a milk processing plant--Wisconsin. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 35 (17): 274-275.

11. Pohanish, R.P. (2012, October 21). Sittig’s Handbook of Toxic and Hazardous Chemicals and Carcinogens. (6th ed.) Chem-Data Systems.