The challenges posed by a biological incident and corresponding response and recovery strategies will largely depend on the pathogen involved, its mode of transmission, the availability of MCMs, and the intentionality (e.g., accidental vs. malicious) of the release. A wide range of incident types are possible, from incidents that harm just one person in a single location, to a pandemic infecting millions globally. While this range greatly influences response and recovery considerations for planners, in all cases, key considerations should be based on the biological agent’s potential to cause harm to humans, animals, or the environment. Described as examples below, past domestic and international incidents illustrate the wide range of potential scope, scale, and response needs for different types of biological incidents.

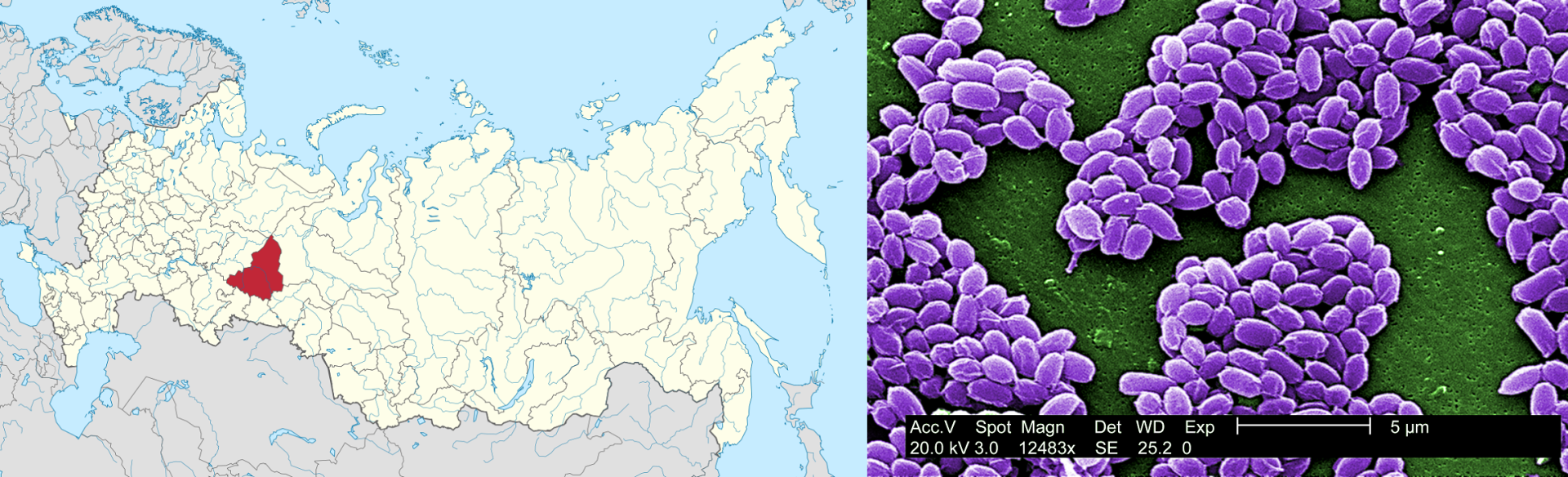

Sverdlovsk Anthrax Outbreak (1979)4

In April 1979 in Sverdlovsk, Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), animals, including livestock, began dying from anthrax, with no identified environmental source. Shortly thereafter, doctors began to report illnesses and deaths in humans from anthrax. The origin of the anthrax in humans was initially reported to be contaminated meat; later, scientists observed that most of the humans and animals affected lived within a narrow zone downwind of a nearby military facility and determined that this military facility had accidentally released anthrax spores into the air.

This incident represents the largest documented outbreak of human inhalation anthrax, with 96 cases leading to 64 deaths, and demonstrates how a biological release may not be recognized for some time, during which the extent of the hazard and the source/cause of the incident will remain unclear. Further, the incident demonstrates how biological agents may move (especially via water or air) and persist in the environment and how they can affect the health of both human and animal populations within a community.

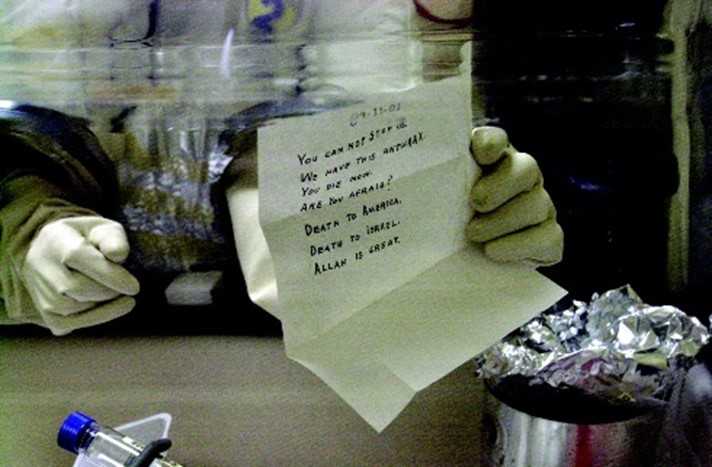

Amerithrax (2001)6

The Amerithrax incident of 2001 represents the malicious use of a biological agent and the potential for intentional biological incidents to cause outsized harm to society and to engender fear among U.S. citizens. On October 3, 2001, an employee of Florida American Media, Inc. was diagnosed with inhalational anthrax; he died two days later. Soon after, anthrax spores were found in the office where the employee worked. This man’s death, along with multiple suspicious letters found within the postal system around the same time (one of which potentially reached the man’s office), triggered a U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) investigation. Additional contaminated letters were sent to the New York Post and NBC News in New York City, where they sickened multiple media organization employees and U.S. Postal Service (USPS) workers.

Three weeks later, letters laced with anthrax spore-containing “white powder” were sent to U.S. senators Daschle and Leahy at their Washington, D.C., offices. The letter to Senator Daschle was opened in Hart Senate Office Building on October 15, 2001, triggering evacuations, mass prophylaxis of government employees, and subsequent building decontamination. The letter to Senator Leahy was not discovered initially and was not recovered until a month later.

Contamination due to the circulation of these letters within the USPS system resulted in five deaths and sickened 22 others. The incident, one of the worst biological attacks in U.S. history, spurred the closing of 35 commercial mailrooms and postal facilities along with 26 buildings on Capitol Hill for investigation and decontamination. Due to the potential for widespread USPS worker exposure, more than 3,000 postal workers in New York, New Jersey, and Washington, D.C., were prescribed an emergency course of prophylactic antibiotics. While the discrete location of each incident allowed for a tailored response to this intentional attack, the accompanying fear affected many, and the expense of necessary site decontamination activities was great.

Ebole Virus Disease (2014)8

In August 2014, an Ebola virus disease (EVD) outbreak in West Africa was declared a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) by the World Health Organization (WHO). At the time of the PHEIC declaration, this was the largest EVD outbreak ever recorded. The outbreak involved transmission in Guinea, Liberia, Nigeria, and Sierra Leone, with these four countries reporting 1,779 cases, including 961 deaths.9

On September 25, 2014, a man visiting Dallas, Texas, sought treatment at the Texas Presbyterian Hospital emergency department. He was initially diagnosed with sinusitis and unspecified abdominal pain and sent home with antibiotics. Three days later, the man’s symptoms had worsened, and he was transported by ambulance back to the hospital. This time, the doctor noted the man had recently traveled from Liberia and ordered a test for Ebola virus infection. The doctor also contacted the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). On September 30, the HHS CDC announced the man was diagnosed with EVD, making it the first laboratory-confirmed Ebola case diagnosed in the U.S. The man’s condition worsened despite the provision of critical care and experimental drug treatment, and he died on October 8. Local public health officials conducted contact tracing of the patient, and all 177 known contacts were monitored for 21 days.

Two healthcare workers who cared for the patient discussed above at Texas Presbyterian Hospital subsequently developed symptoms, and both tested positive for Ebola virus infection. Due to the potentially high mortality rate of EVD, these two healthcare workers were transferred to highly specialized treatment centers at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Clinical Center in Bethesda, Maryland and Emory Hospital in Atlanta, Georgia, respectively, and both recovered. Also in October 2014, the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene reported a case of EVD in a physician who had just returned from Guinea where he served with Doctors Without Borders. The physician was treated at Bellevue Hospital Center and discharged. Contact tracing and quarantine measures were implemented for people in contact with each of the three healthcare workers that developed EVD infections. In addition, the physician’s apartment and the bowling alley he visited the day before his hospitalization required decontamination.

The intense resource requirements necessary for treating, quarantining, contact tracing, decontaminating, and mass public messaging in incidents involving diseases with high mortality rates may quickly surpass most local response capabilities. In 2014, Ebola was handled by local authorities reporting to state and federal authorities, which enabled national coordination across states. This incident also highlights the possibility for public fear of a disease to take hold. While Ebola is a serious and deadly disease, according to the HHS CDC, a person can only spread Ebola to other people after developing signs and symptoms, with EVD posing little risk to travelers or the general public who have not cared for or been in close contact with someone sick with Ebola.10 Risk communication is critical to effective biological incident response and recovery.

Coronavirus Disease 2019 (2020)11

At the time of writing this document, the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic is ongoing and has caused the deaths of more than 6 million people worldwide.12 The first COVID-19 cases in the U.S. were identified at the end of January 2020 and were associated with travel to China. The Secretary of HHS declared a public health emergency on January 31, 2020. Community transmission of COVID-19 was first documented in Seattle, Washington, when the first non-travel-related case of COVID-19 in the U.S. was confirmed on February 28, 2020. In response to the growing risk of widespread disease transmission throughout the U.S., the President declared a nationwide emergency under the Stafford Act in March 2020. This Stafford Act declaration was associated with the formation of a Unified Coordination Group (UCG) led by the Federal Emergency Management Agency.

Without a vaccine or specific treatment available initially, patients with COVID-19 received supportive care in isolation, and exposed individuals were quarantined. NPIs such as mask wearing, contact tracing, social distancing, restricting visitors at hospitals, and restricting travel to infection hotspots were employed to help mitigate disease spread. After a multidisciplinary effort for rapid vaccine development supported by the federal government, academia, and industry, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued an emergency use authorization for the first COVID-19 vaccine on December 11, 2020. Similar authorization followed rapidly for other vaccines, and a nationwide vaccine distribution campaign for adults began.

The introduction of COVID-19 into the U.S. serves as warning for how easily international disease outbreaks can spread across the globe. The COVID-19 experience also highlights the challenges posed by novel or emerging infectious diseases that are contagious from person to person. Two years after the outbreak began, COVID-19 cases continue to challenge healthcare capacities as viral variants emerge and spread. Hospitals in infection hotspots continue to experience staff shortages due to illness and exposure. Meanwhile, the ongoing pandemic continues to strain local and federal response agencies working to protect the nation’s health and safety while maintaining the stability of the workforce and the economy. This incident also demonstrates how international travel can rapidly spread communicable diseases worldwide, how a biological incident can seriously disrupt critical infrastructure and global supply chains, how public perception of an incident can impact response and recovery efforts, and how the healthcare sector is essential to the response even while its workers are particularly vulnerable to pathogen exposure.