2.1. Flooding at a Chemical Plant

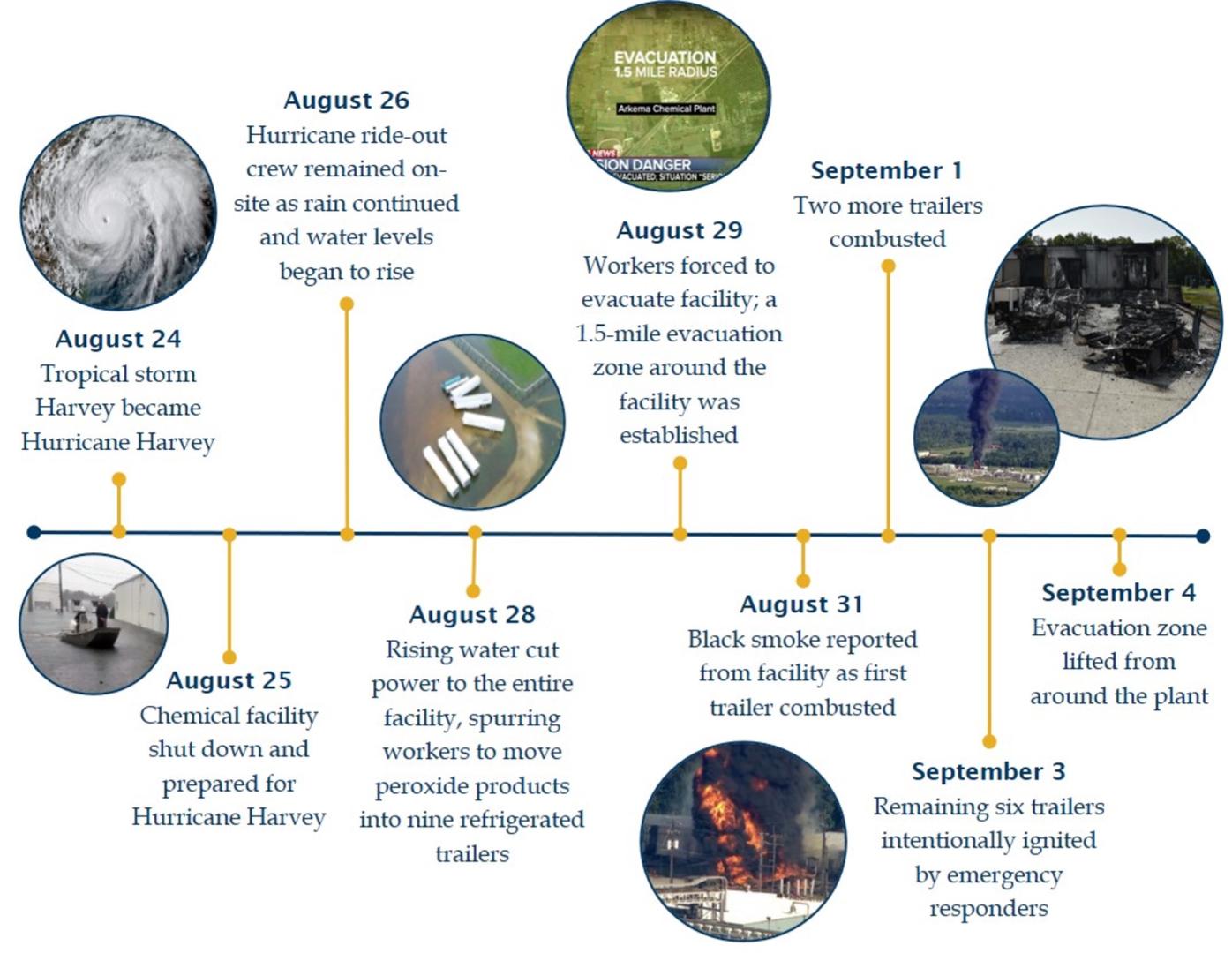

In the wake of Hurricane Harvey in late August 2017, extreme flooding at a chemical plant in Crosby, TX, led to a series of events that culminated in the spontaneous combustion and release of peroxide compounds.3 By the time the all-clear was given in early September, in excess of 350,000 pounds of organic peroxide had burned, and more than 200 residents evacuated from within 1.5 miles of the facility had been out of their homes for a week.

As Harvey bore down on Texas, employees prepared the facility to ride out the storm. Flooding in the area was not unusual, but floods had never disabled the safety systems in place. This time, unimaginable amounts of rain would fall, and the resulting flooding would exceed equipment design elevations. In this case, multiple layers of protection failed despite highly trained workers remaining on-site to implement the facility's preparedness plans – which were, unfortunately, still inadequate.

The plant lost power, backup power, and critical refrigeration systems, with catastrophic results. Without refrigeration, some of the organic peroxide compounds on site combusted in just a few days, releasing toxic smoke into the surrounding area. Hampered by the damage and closures wrought by the hurricane, plant personnel and local emergency responders had few options to ensure a speedy and safe conclusion to the incident. They elected to plan and perform a controlled burn of the remainder of the facility's compounds.

Emergency response officials had initially decided to keep the local highway open because it served as an important route for hurricane recovery efforts in the area even though it ran through the evacuation zone around the facility. Eventually, five police officers in four vehicles driving down the highway toward the facility reported being exposed to a smoke cloud coming from the facility; they quickly experienced nausea, headaches, sore throats, and itchy watering eyes, and requested medical assistance. Following this event, all travel on the highway was stopped. In all, 21 people sought medical attention from exposure to toxic fumes generated by the decomposing peroxides.

The plans, efforts, and experience of facility employees were not enough to stave off a flooding disaster, particularly one beyond the imagination of the plant's safeguard planners.

2.2. Chemical Leak into Waterway

On January 9, 2014, 11,000 gallons of crude methylcyclohexanemethanol (MCHM) leaked from a corroded tank at a chemical storage and distribution site in Charleston, WV, into the nearby Elk River.4 The substance flowed downstream, quickly traveling the 1.5 miles to the intake for the West Virginia American Water (WVAW) water treatment facility. A week later (January 17), MCHM was detected as far as 400 miles downriver, in Louisville, Kentucky.5

The incident was recognized because of the resulting odor, first by the public (in the morning) and then by WVAW (in the afternoon). Based on initial, mistaken information regarding the identify and quantity of the leaked substance, WVAW assumed its system was capable of fully treating and removing the chemical from the water. Later that afternoon, WVAW realized that in fact, it could not, and the drinking water within WVAW’s distribution system was contaminated.

A Do Not Use (DNU) order was issued for ~300,000 residents across portions of nine counties, restricting usage of tap water for drinking, cooking and bathing for four to nine days. The DNU order resulted in closures of many businesses, schools and public offices. During this time, FEMA, the West Virginia National Guard, first responders, city governmental agencies, civic groups and multiple state agencies worked together to ensure affected residents had water available: more than 2 million one-gallon jugs and nearly 30 million bottles of water were distributed to the public. The geographic and economic extent of the effects and the need for coordinated response led to the declaration of an emergency via the Stafford Act on January 10.

Response to the incident was further plagued by misinformation. In fact, it was after the DNU was lifted – 12 days after the leak – that the site operators announced that a mixture of polyglycol ethers (PPH) had been released along with the MCHM, because they were stored within the same tank. Neither emergency responders nor WVAW had been provided with safety data sheets (SDS) for PPH, a substance known to cause adverse health effects, during the incident.

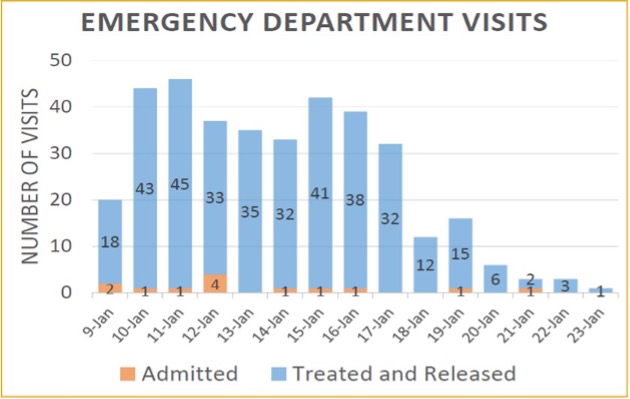

Over the 2 weeks following the spill, area public health officials noted a surge of several hundred patients experiencing nausea, rashes, vomiting, abdominal pain and diarrhea following exposure to the water through inhalation, ingestion and/or skin contact. These patients were treated and released.

Residents in the Charleston area were given unclear and conflicting advice due to available information changing over the course of the incident. Some residents noticed an unpleasant odor in the water for several weeks following the leak, even after flushing piping as directed. As a result, many residents did not believe the water was safe to drink after water restrictions were lifted.

Footnotes

3. CSB. (2018, May). Organic Peroxide Decomposition, Release, and Fire at Arkema Crosby Following Hurricane Harvey Flooding. Report Number: 2017-08-I-TX.

4. CSB. (2017, May). Chemical Spill Contaminates Public Water Supply in Charleston, West Virginia. Report Number: 2014-01-I-WV.

5. Foreman, W.T., Rose, D.L., Chambers, D.B., Crain, A.S., Murtagh, L.K., Thakellapalli, H. et al. (2015). Determination of (4-methylcyclohexyl) methanol isomers by heated purge-and-trap GC/MS in water samples from the 2014 Elk River, West Virginia, chemical spill. Chemosphere, 131, 217-224.