During a biological incident, effective response and recovery is directly linked to compliance with public health guidance regarding personal protective measures and public perception of access to health and medical interventions. Therefore, public communications must synthesize complex medical and health information to promote public understanding of and compliance with such guidance. In addition to all-hazards communication principles, biological incident communications should:

- Provide actionable guidance to the public, healthcare workers, and first responders/receivers on safe work practices, PPE, and steps the public should take to protect itself

- Anticipate and address the questions, concerns, and differing perspectives of the public, business owners, elected officials, and health officials when communicating public health risks and risk prevention measures

- Anticipate and actively monitor mis- and disinformation in mass media and on social media platforms

- Maintain empathetic and validating two-way communication between decision makers and the public

- Support public awareness of ongoing cleanup activities and ongoing human, animal, and environmental health risks

- Coordinate associated messaging for all the above with stakeholder organizations involved

The public will demand authoritative, timely, and accurate information, even in the context of a fluid situation that is still developing. Effective response and recovery communication are fostered by comprehensive and flexible communication plans, strategies, and content developed prior to an incident. Coordinated, accessible messaging and information that adheres to principles of risk communication, even in areas unaffected by the incident, is crucial for combating the public fear and anxiety that often characterizes biological incidents. Remember that public communications during biological incident response may include both human and animal health guidance and will likely be more complex than most emergency messages. Maintaining public trust and compliance with warnings and guidance will continue to be a key objective of communications activities during incident response and recovery due to the unique characteristics of biological incidents and the time needed to identify the causative biological agent in many instances.

2.2.1 Public Information Focus

- Specific – Provide the public with clear information to understand the risk (e.g., confirmed vs. suspected identity of the biological agent) and how to follow specific public health guidance.

- Consistent – Messages should not contain contradictory information, and messaging should be consistent across all communication channels available to the public. Message coordination between public health and emergency management officials as well as other stakeholder organizations should occur prior to information dissemination to the public.

- Certain – State what is known and unknown in certain terms (i.e., location of origin of dispersal, etc.). Do not guess or speculate.

- Clear – Use common words that can easily be understood and avoid technical terms.

- Accurate – Do not overstate or understate the facts or omit important information. For example, be accurate when sharing case rates, and explain how that information was collected. Clearly communicate that guidance will be updated as data, resources, and science change.

- Accessible – Craft messages with consideration for people with disabilities (e.g., vision- or hearing-impaired populations) and for non-English speaking individuals.

Message context should also be clear to the audience and accompany the guidance. Understanding the hazard, location, timeframe, source of warning, etc. allows for better understanding of the messaging and subsequently helps to mitigate the impacts of the biological incident. Messages should include the following context:

- Specific hazard – What is the biological hazard? What are the potential risks for the community?

- Location – Where will the effects occur? Does the incident involve a discrete or wide-area dispersal? Is the location described so those without local knowledge can understand their risk?

- Timeframe – When will the effects of the biological incident present themselves? How long will the effects last? Is there time to implement protective actions (e.g., masks, movement restrictions, etc.)?

- Source of warning – Who is issuing the warning? Is it an official source with public credibility? Is a SME, such as virologist or scientist, available to facilitate public communication?

- Magnitude – A description of the expected effects. How bad is it likely to get? How far and how quickly could the biological agent potentially spread?

- Likelihood – The probability of occurrence of the effect. For intentional attacks, what is the likelihood of a secondary attack?

- Protective behavior – What protective actions should people take and when? Where/who should (or should not) take the actions (described in clear geospatial, age group, and other everyday terms)? How will the protective actions reduce the biological agent’s impact? If evacuation is called for, where should people go and what should they take with them?

Keep messaging language simple and easy to understand to help ensure people take the right protective actions at the right times. For example, what type of mask to wear and when to wear it. People will want to know why an action is protective before they will take that action.

What Will You Need to Know?

- Who will gather and synthesize medical and health information for public guidance and compliance from SLTT, federal, non-governmental, and private sector partners?

- When is that likely to happen based on the established response timeline?

- How will various stakeholders be engaged based on specific biological agent types?

- Which stakeholders will be engaged if the incident is thought to be intentional?

- How will information on availability of MCMs be provided to the public? On locations of supportive care and treatment facilities? On instructions on risk and protective measures? On testing site and availability?

2.2.2 Public Information Delivery

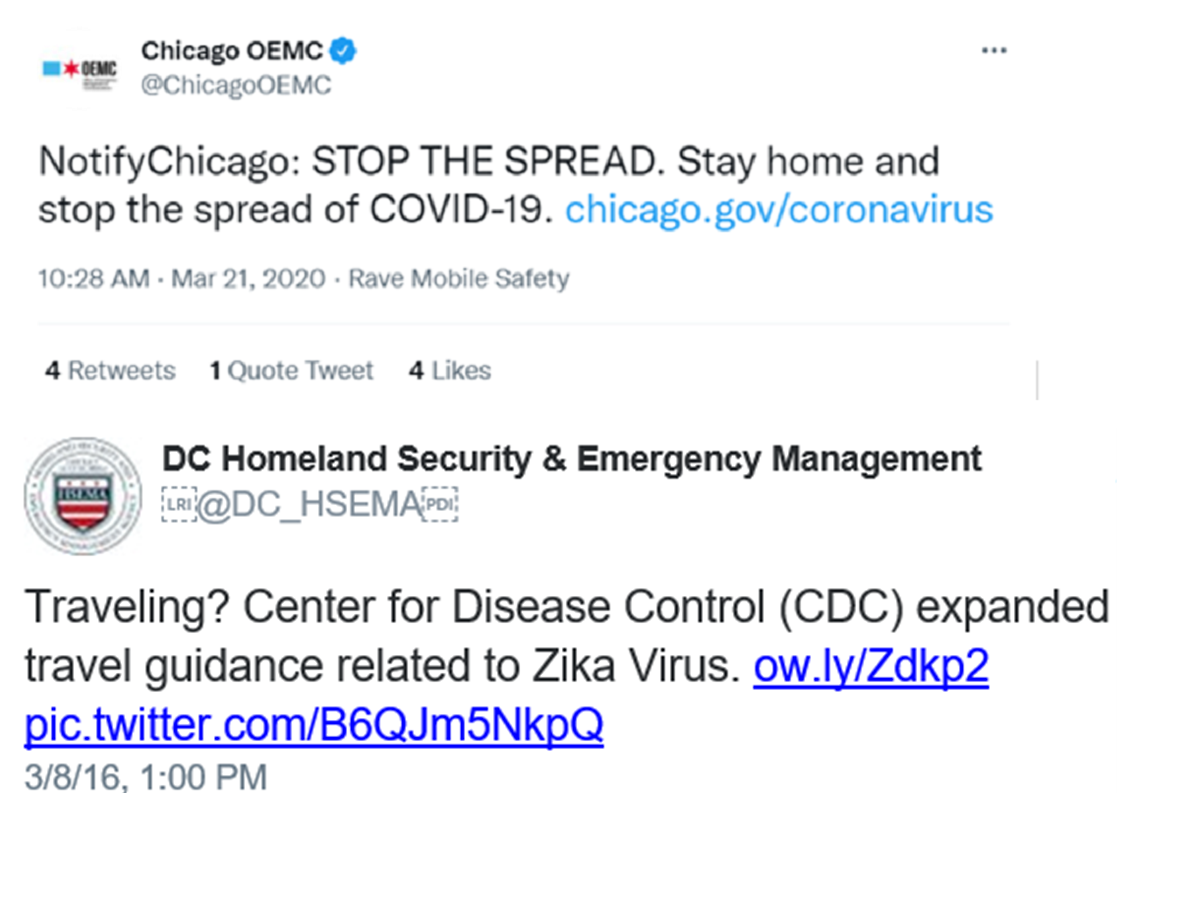

Before an incident, jurisdictions and agencies should identify communication systems for public messaging for use in providing clear, factual, and timely public health and safety guidance. In general, dissemination channels should be agile and immediate and able to handle frequent updates as information changes and becomes available. Information can be disseminated through several means including social media, traditional media, and press conferences.

For incidents involving multiple agencies, incident leadership may establish a Joint Information Center (JIC). The Public Information Officer (PIO) participates in or leads the JIC. The JIC is where personnel with public information responsibilities collaboratively perform essential public information and public affairs functions. Leaders can establish a JIC as a standalone coordination entity, as a component of an EOC, or virtually. Typically, a single JIC is sufficient, but the system is flexible enough to accommodate multiple physical or virtual JICs. For example, multiple JICs may be necessary for a biological incident covering a wide geographic area or multiple jurisdictions.

Plans should include a standard operating procedure that can be easily integrated into existing communication plans for the specific methods and partnership networks that will be used to communicate information and protective action directives within the jurisdiction during a biological incident. The methods chosen should be informed by typical community usage of platforms and outlets and communicated to the public during preparedness campaigns so that they know where to receive emergency information. Such an approach will help reduce instances of community members using unreliable sources of information and delaying protective action. Additional considerations should be made for how to reach different at-risk populations, as biological incidents pose varying threats to specific populations (e.g., those who are immunocompromised).

For immediate emergency notification, SLTT communications staff can take advantage of public alerting systems that they may use for other incidents (e.g., FEMA’s Integrated Public Alert and Warning System [IPAWS], the Emergency Alert System, etc.). For example, the use of geo-targeted messaging or IPAWS, which has the capability to broadcast an alert message to all cellular phones in a given area as a Wireless Emergency Alert (WEA), can provide evacuation, stay-at-home, or other protection guidance to those in an affected area. The limitations of these systems, including the frequency of messaging and the language options available, should be explored, and mitigation strategies considered in advance.

Additionally, planners should consider how to ensure information delivery during concurrent disasters for their communities. For example, cellular connectivity may be lost for days after a natural disaster such as a hurricane or an earthquake in the same area that is being impacted by a concurrent biological incident.

What Will You Need to Know?

- How will you contact hard-to-reach populations that are considered “high risk” for contracting a biological agent (transient, those experiencing homelessness, homebound, etc.), if the agent is contagious?